March 2021

Improving appropriateness of Red Blood Cell transfusions: The START (Screening by Technologists and Auditing to Reduce Transfusion) study

Amie Kron, MSc

Clinical Research Coordinator, Department of Transfusion Medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre

QUEST Transfusion Research Program, University of Toronto

Dr. Jeannie Callum, MD, FRCPC

Transfusion Medicine Specialist and Hematologist at Kingston Health Sciences Centre and Professor in the Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine at Queen’s University

Lead, QUEST transfusion research program at the University of Toronto, Professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at the University of Toronto.

(On behalf of the START study investigators)

Promoting blood product conservation, including minimizing unnecessary use of red blood cells (RBC), is a primary focus of the University of Toronto QUEST (Quality in Utilization, Education and Safety in Transfusion) Research Program. Red blood cells are transfused to approximately 10% of hospitalized patients, and 1 in 4 to 5 transfusions are reported as unnecessary. Considering the risk of adverse transfusion reactions, activity based costs of $700/unit, and reliance on donors for a safe blood supply, the group led a quality improvement study to reduce the levels of unnecessary RBC transfusions.

To identify hospitals who would benefit from a multi-faceted intervention to reduce inappropriate RBC use, medical chart audits of 10 consecutive RBC transfusions/month for the duration of 5 months were conducted in 15 large and primarily community hospitals. Using a restrictive set of RBC transfusion guidelines, two hematologists blindly and independently adjudicated RBC transfusions for appropriateness. Thirteen hospitals across three provinces had a baseline appropriateness <90% and qualified to participate in the intervention portion of the study.

The intervention launch took place over 3-months and included the following: (1) implementation and education of standardized RBC guidelines through online (e.g., PowerPoint talks, screensavers, flyers) and in-person methods; (2) prospective MLT screening of blood cell orders during the daytime to flag inappropriate orders requiring approval from the local site champion prior to issue; and (3) monthly auditing of transfusions for appropriateness along with feedback from the clinical team. Hospitals were supported to adopt a restrictive transfusion threshold for hemodynamically stable inpatients – single unit transfusions for hemoglobin levels under 70 g/L or under 80 g/L for patients with known cardiac disease. After the intervention, a 10-month audit identical to the baseline audit occurred with the shift to 24/7 screening by MLT for RBC transfusion orders. The central study coordinator sent monthly appropriateness reports to each site to indicate their proportion of appropriate transfusion orders.

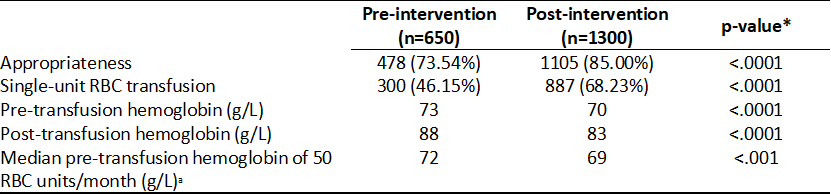

Implementing this quality improvement study had a positive impact on the reduction of RBC utilization across the 13 participating hospitals in Canada. The study audited 1,950 patients and 2,877 transfused RBC units. Pre-intervention, 26.5% of RBC units transfused were adjudicated as inappropriate. Pre- to post-intervention, the proportion of appropriate transfusions and single-unit transfusions increased. A reduction in pre- and post-transfusion hemoglobin levels was also seen, along with a decrease in the median pre-transfusion hemoglobin based on 50 consecutive RBC units transfused/month (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of findings

* statistically significant (p<.05)

a Pre-intervention (n=3075), Post-intervention (n=6049)

The number of RBCs transfused decreased significantly with an average decrease of 458 units per month. Despite advocating for a restrictive transfusion approach, this study had no impact on under-transfusion (hemoglobin <60 g/L). The restrictive approach also had no impact on length of stay, need for ICU support, or in-hospital mortality. This data in conjunction with the results of other blood conservation studies suggests that a restrictive threshold is non-inferior to a liberal threshold.

Implementing this intervention led to an overall reduction in the use of approximately 5000 RBCs over 10 months at 13 hospitals. This translates into an estimated activity-based cost savings of $3.1 million. Evidently, the initiatives used in this study have the potential to optimize blood utilization in hospitals with high rates of inappropriate blood use. Appropriate blood component use translates into better patient and donor outcomes, and helps maintain Canada’s blood supply. There is a pressing need to generalize this study to the rest of Canada to help improve overall blood management within the Canadian healthcare system. With the efforts of Choosing Wisely Canada and Canadian Blood Services, the Using Blood Wisely campaign has been informed by the results of the START study and launched to reduce inappropriate RBC transfusions and improve general transfusion practice across Canada.

Registration now open:

April 14th: 16th Annual TM Education Web Conference

April 30th: Ontario’s First Recommendations for Massive Hemorrhage Protocol Virtual Symposium

The value-proposition for quality improvement in the care of the massively hemorrhaging child

Kimmo Murto MD1,2, Suzanne Beno MD3,4, Mark McVey MD4,5, Wendy Owens ART, B Comm6 and Lani Lieberman MD7,8

1Associate Professor, University of Ottawa, Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine; 2Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute; 3Associate Professor, University of Toronto, Department of Paediatrics, Division of Emergency Medicine; 4Hospital for Sick Children; 5Assistant Professor, University of Toronto, Department of Anesthesiology & Pain Medicine; 6Program Manager, Ontario Regional Blood Coordinating Network; 7Assistant Professor, University of Toronto, Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathology; 8University Health Network: Toronto General Hospital

This is the second article of a two-part series discussing the soon to be released ORBCoN-sponsored pediatric massive hemorrhage protocol (MHP). As previously stated, pediatric MHPs have demonstrated improved process-related outcomes (e.g. speed of blood product delivery to the bedside), but in contrast to adults, patient outcome benefits in both trauma and elective surgical settings remain elusive. The aim of this article is to summarize pediatric MHP-related aspects of the “value-proposition” in healthcare service delivery quality improvement with the intent to help hospital administrators and clinicians justify the implementation of a pediatric MHP in the absence of demonstrated patient outcome benefits.

Value proposition for a Pediatric MHP

Healthcare systems world-wide including Canada are beginning to transition from “volume” to “value-based” healthcare.1 The United States Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) introduced the “Triple Aim” framework (2006) for overall healthcare reform which was adopted by the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (CFHI) and comprises three interdependent goals: 1. improving the health of populations, 2. improving the healthcare of the individual including their experience and 3. reducing per capita costs of care.2 The current healthcare system is financially unsustainable as health spending growth continues to outpace economic growth.3 Further, there is evidence for declining population health and quality of healthcare service delivery (e.g. access),3,4 creating a “burning platform” to flatten the cost curve through changing reimbursement models such as accountable care organizations. Towards value-based healthcare, the United States introduced pay-for-performance measures in 2010 that include a combination of incentives and penalties using information transparency and quality reporting, clinical informatics and adoption of well-proven protocols/algorithms (e.g. enhanced recovery after surgery or ERAS) to decrease complications and mishaps during hospitalization.5,6,7 Canadian pediatric Quality-Based-Procedures or QBPs (e.g. tonsillectomy or asthma management) are an initial attempt to link funding to an entire cycle of standardized care including outcomes (e.g. return to hospital), however the QBPs are few in number and currently lack the financial penalties required to ensure accountability. As such, Canadian hospitals and providers currently incur minimal financial penalty for poor patient outcomes.8 Recently, many Canadian pediatric hospitals have signed on to pediatric quality improvement networks such as “Solutions for Patient Safety (SPS)”9 and the “National Surgery Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP)”10 advocating to measure, compare and improve the quality of medical and surgical patient care. Unfortunately, the care of the massively bleeding child or adult has yet to be subjected to this degree of scrutiny. 11,12,13 The proposed MHP Tool-box is designed to facilitate this goal.

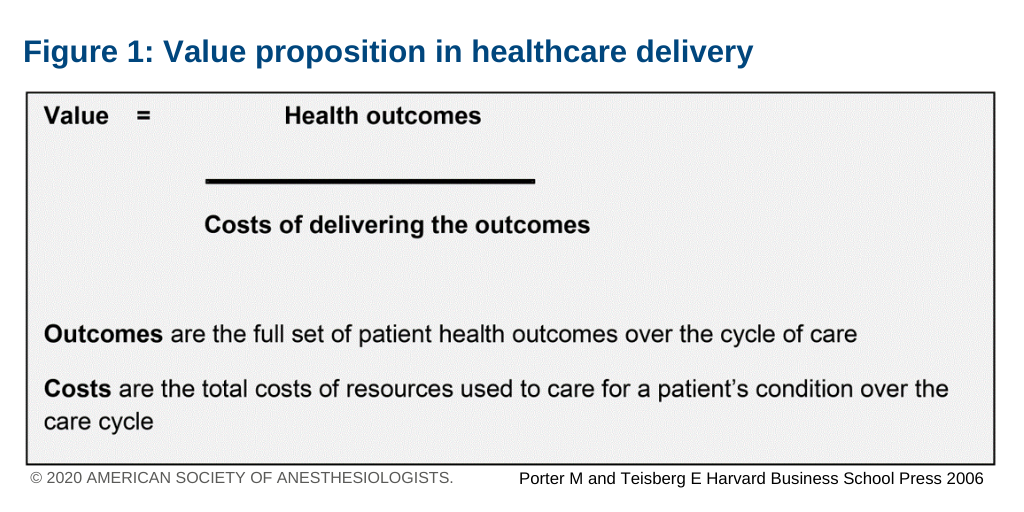

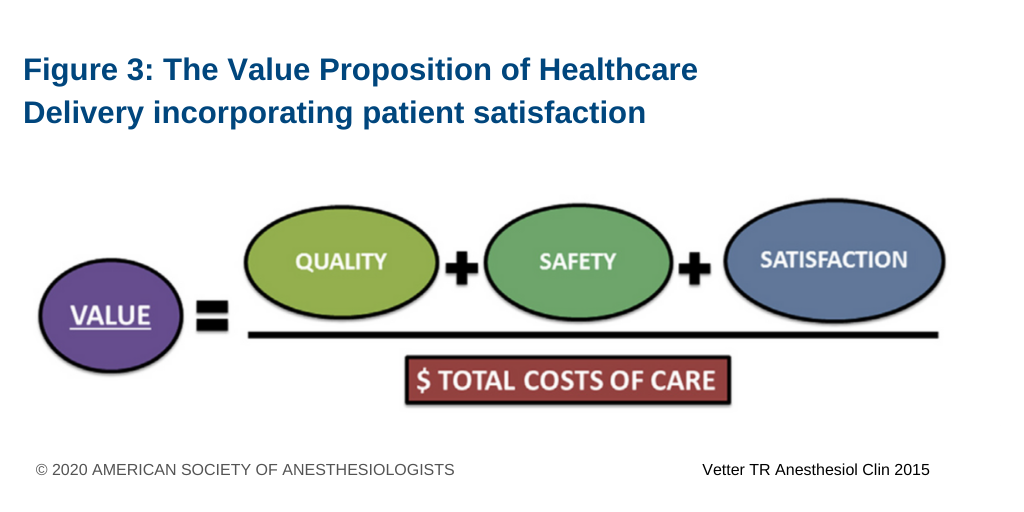

Value in healthcare service delivery incorporates aspects of patient/family satisfaction or experience, quality, safety, and cost and has been defined as health outcomes achieved that matter to patients relative to the costs of achieving those outcomes over a cycle of care (see figure1).14,15 Although the measurement and interpretation of patient satisfaction and experience can be difficult,16 it correlates with health outcomes of which patient important outcomes (PIOs) categorized as either patient reported experience measures (PREMs) or outcome measures (PROMs) have been suggested17 and a generic 3-tiered hierarchy of PROMs has been proposed. 18 When applied to a MHP activation this hierarchy could capture: Tier-1. Health status achieved or retained (e.g. survival), Tier-2. Process of recovery (e.g. immediate complications or time to return to normal activities) and Tier-3. Sustainability of health (e.g. care-induced illness related to a blood product).

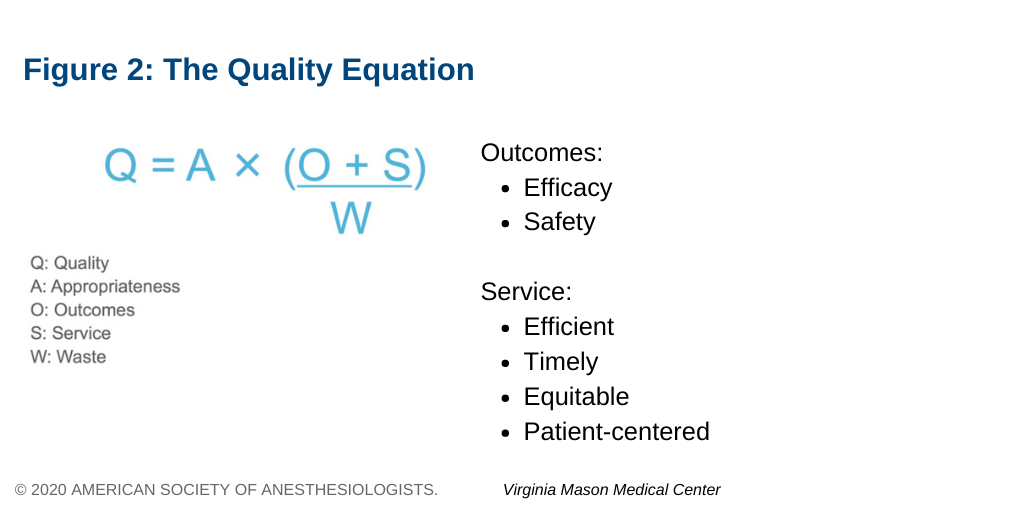

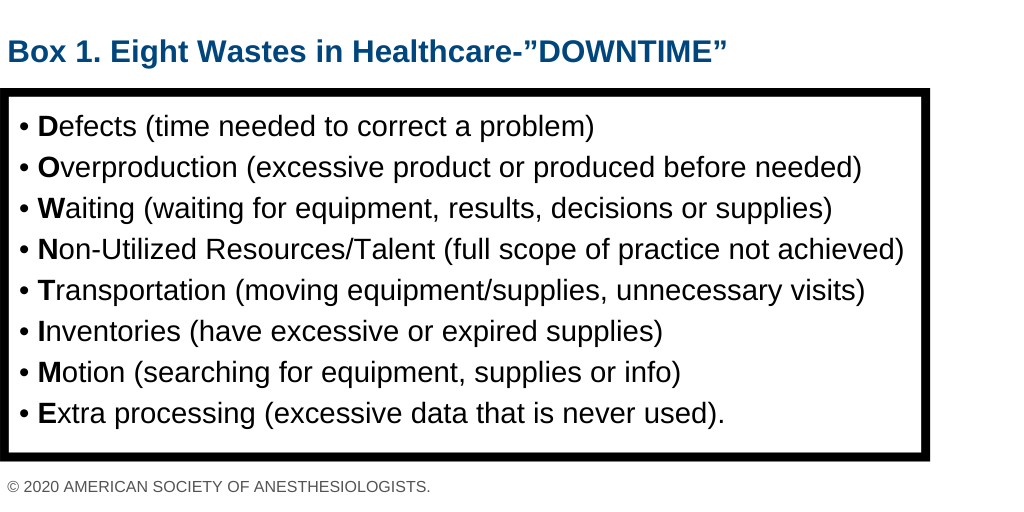

Quality in healthcare service delivery is an often misunderstood term. The Virginia Mason Medical Center, an adopter of “Lean methodology” in healthcare service delivery, utilizes several metrics of quality in their daily practice (see figure 2). The term “outcomes” (provider or patient important) capture aspects of efficacy and safety while “service” refers to healthcare that is efficient, timely and equitable and patient centered. The term “waste” is described by Lean-methodology in the form of an acronym “DOWNTIME” representing the eight wastes in healthcare (Box 1). The product of removing inappropriate and wasteful aspects of care during an MHP activation are high-yield quality improvement multipliers to reduce overall variability in care.19 Figure 3 defines the value proposition for healthcare service delivery as it could apply to a pediatric MHP.5 It is shown that value directly correlates with quality, safety and patient/family satisfaction and is inversely proportional to costs or waste, where an increase in the former or a decrease in the latter (or both) can increase the value of care delivered. To this end, the new MHP Tool-box is advocating for mandatory reporting of 8 quality measures, with three process measures at the provincial level capturing MHP compliance (i.e. timely administration of tranexamic acid, RBCs and transition to group-specific RBCs and plasma) and the rest reported locally and related to both process (e.g. blood product wastage) and patient outcomes (e.g. survival). Still pending, however, are quality measures of patient safety (e.g. administration of incompatible blood product or hyperkalemia treatment) or yet to be determined patient/family important outcomes beyond survival.

Although it is widely accepted that poor quality increases cost it is less clear that improvement in process and/or patient outcomes reduces costs, the conundrum being that to improve quality may require additional funding (e.g. upgrading an electronic medical record). The “Lean methodology” for QI suggests than an upfront focus on quality improvement (e.g. reducing inappropriate or wasteful care) will naturally lead to later cost reductions in healthcare service delivery.15 From a physician’s perspective proposed cost cutting is more palatable when framed in terms of trust-worthy data and a waste reduction approach. Evidence from the adult and pediatric enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) literature suggest that a standardized evidence-based in-hospital protocol with clearly defined elements and goals of patient optimization and surgical stress response reduction enhance interdisciplinary communication, decreases length of stay, improves recovery, minimizes complications and is associated with cost-savings.6,7,20 Similarly, the proposed ORBCoN MHP should be considered as an enhanced recovery after massive hemorrhage care pathway. The extent of cost savings will be hospital-specific and will depend on the extent of hospital leadership buy-in for QI methodology implementation.

Implementation and sustainability of a MHP in a clinical setting can be a complex undertaking. Unfortunately, there is no reported evidence-based approach for successful MHP implementation.21 It requires familiarity with a staged change management process (e.g. John Kotter methodology).22 A common framework for QI projects is the recurrent continuous improvement “Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA)” cycle.23 Front-line clinicians and staff are most familiar in caring for these patients and are well positioned to determine best care in their clinical context. Patient/family representation in this process is ideal. Examples of MHP implementation in clinical settings24,25,26, reveal they can be up to 12 months, and are usually initiated by a multi-disciplinary team, provide reference to clinician education, require an assessment of site-specific barriers to implementation and importantly require sponsorship by the hospital executive.7,27 The MHP tool-kit is expected to provide readers with resources to identify barriers to implementation and strategies to overcome them. Critically, a recurring “feedback loop” is required to collect provider feedback, patient outcomes and quantitative service (e.g. TXA administration) and hospital centric data (e.g. LOS or complications) to optimize patient outcomes and confirm protocol compliance. Success is determined when all three criteria of improved quality, reduced cost (waste) and increased front-line provider morale are achieved.15 The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) can be used to disseminate MHP implementation success internally or in a scholarly format externally to other health care organizations.28

Conclusion

Quality is increasingly a greater focus for Canadian healthcare service delivery payers including the various Provincial Ministries of Health and private insurance. Surrogate adult evidence suggests that in addition to improved patient outcomes, a reduction in complications and a potential for cost savings are to be expected with implementation of a pediatric MHP. As such, implementation should follow a three-staged process involving planning, implementing and sustaining change to overcome typical barriers related to provider knowledge, attitude and beliefs. The format of the pediatric MHP is similar to the adult version for the sake of familiarity and ease to implement into a community setting. While a plan is in place to code for MHP activation through Canadian health administrative data (HAD), it would benefit from the concomitant development of an Ontario MHP activation repository to validate these cases (adult and pediatric) and capture safety-related quality measures such as fluid overload and hyperkalemia treatment specific to children. As patient/family centered outcome measures may provide insight into aspects of MHP care that are harmful and require adjustment, the current Ontario Pediatric Patient Experience of Care Survey should also be adapted to capture transfusion-specific patient/family PREMs, such as wrong-blood product administration, evidence of improper patient identification prior to transfusion or being provided a summary of in-hospital administered blood products. The introduction of sophisticated electronic medical records (EMR) (e.g. EPIC) will allow for post-discharge electronic survey administration to capture Tier-2 PROMs associated with quality of life (QOL) (e.g. PedsQL™) and HAD (e.g. IC/ES) will provide insight into Tier-3 outcomes related to long-term related health-care service delivery utilization. Beyond likely becoming a future hospital accreditation requirement, a common MHP will ensure an equitable and higher standard of care province-wide to the massively bleeding child.

References

1 Porter ME, Lee TH. From Volume to Value in Health Care The Work Begins. JAMA – J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016;316(10):1047–8.

2 Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–69.

3 Abrams RTMK. U . S . Health Care from a Global Perspective , 2019 : Higher Spending , Worse Outcomes ? New York, NY; 2020.

4 Eric C Schneider DS. From Last to First – Could the U.S. Health Care System Become the Best in the World? N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377(10):901–4.

5 Thomas R. Vetter KAJ. Perioperative Surgical Home: Perspective II. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2015;33(4):771–84.

6 Olle Ljungqvist, Michael Scott KCF. ‘Enhanced Recovery After Surgery A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):292–8.

7 Rove KO, Edney JC, Brockel MA. Enhanced recovery after surgery in children : Promising, evidence-based multidisciplinary care. Pediatr. Anesth. 2018;28:482–92.

8 Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care & Provincial Council for Maternal & Child Health. Quality-Based Procedures Clinical Handbook for Paediatric Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy [Internet]. 2016. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ecfa/docs/qbp_tonsil.pdf

9 Lyren A, Coffey M, Shepherd M, Lashutka N, Muething S. We Will Not Compete on Safety: How Children’s Hospitals Have Come Together to Hasten Harm Reduction. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. Elsevier Inc.; 2018;44(7):377–88.

10 Bruny JL, Hall BL, Barnhart DC, Billmire DF, Dias MS, Dillon PW, et al. American college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program pediatric: A beta phase report. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2013;48(1):74–80.

11 Livingston MH, Singh S, Merritt NH. Massive transfusion in paediatric and adolescent trauma patients: Incidence, patient profile, and outcomes prior to a massive transfusion protocol. Injury. 2014;45(9):1301–6.

12 Chin V, Cope S, Yeh CH, Thompson T, Nascimento B, Pavenski K, et al. Massive hemorrhage protocol survey: Marked variability and absent in one-third of hospitals in Ontario, Canada. Injury. 2019;50(1):46–53.

13 Kamyszek RW, Leraas HJ, Reed C, Ray CM, Nag UP, Poisson JL, et al. Massive transfusion in the pediatric population: A systematic review and summary of best-evidence practice strategies. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(4):744–54.

14 Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 2006.

15 Toussaint JS, Berry LL. The promise of lean in health care. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013;88(1):74–82.

16 Matthew P. Manary, William Boulding, Richard Staelin SWG. The Patient Experience and Health Outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(3):201–3.

17 Raveendran L, Koyle M, Brindle M. Developing a Value Based Approach to Outcome Reporting in Pediatric Surgery. Healthc. Pap. 2019;18(4):20–7.

18 Porter ME. What Is Value in Health Care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–81.

19 Reyes M, Paulus E, Hronek C, Etinger V, Hall M, Vachani J, et al. Choosing Wisely Campaign: Report Card and Achievable Benchmarks of Care for Children’s Hospitals. Hosp. Pediatr. 2017;7(11):633–41.

20 Cannesson M, Kain Z. Enhanced recovery after surgery versus perioperative surgical home: Is it all in the name? Anesth. Analg. 2014;118(5):901–2.

21 Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: Diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement. Sci. 2019;14(1):1–15.

22 Kotter J, Cohen D. Heart of Change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 2002.

23 Health Quality Ontario. Getting Started Guide: Putting Quality Standards Into Practice [Internet]. 2017. Available from: http://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/documents/evidence/quality-standards/getting-started-guide-en.pdf

24 Hendrickson JE, Shaz BH, Pereira G, Parker PM, Jessup P, Atwell F, et al. Implementation of a pediatric trauma massive transfusion protocol: One institution’s experience. Transfusion. 2012;52(6):1228–36.

25 Cotton BA, Dossett LA, Au BK, Nunez TC, Robertson AM, Young PP. Room for (Performance) improvement: Provider-related factors associated with poor outcomes in massive transfusion. J. Trauma – Inj. Infect. Crit. Care. 2009;67(5):1004–11.

26 Nunez TC, Young PP, Holcomb JB, Cotton BA. Creation, implementation, and maturation of a massive transfusion protocol for the exsanguinating trauma patient. J. Trauma – Inj. Infect. Crit. Care. 2010;68(6):1498–505.

27 Drew JR, Pandit M. Why healthcare leadership should embrace quality improvement. BMJ. 2020;368:2015–7.

28 Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016;25(12):986–92.

Upcoming Event:

March 25th: FP Analysis, START Study Results presented by Dr. Aditi Khandelwal and Ms. Amie Kron.